Centre State Legislative Relations, as laid down in India’s Constitution, are important for maintaining a balanced federal system. These relationships include territorial and subject-wise distribution of legislative powers and parliamentary legislation in state matters under specific conditions. To ensure smooth functioning, the Constitution also provides specific guidelines and exceptional circumstances under which the Centre can legislate in state territory, making it a flexible system. In this article, you will learn about different types of Legislative Relations between centre and state, which is very important topic for GS Paper-2 Polity & Governance of UPSC CSE Prelims and Mains Exam. To explore more interesting UPSC Polity concepts similar to center state relations, check out other articles of IASToppers.

Table of Content

- Introduction

- Legislative Relations

- Territorial extent of Central and state legislation

- Distribution of Legislative Subjects

- Conflict between Subjects mentioned in Central, State and Union List

- Comparing with other countries constitution

- Conclusion

- FAQ on Legislative Relations between Centre-State

Introduction

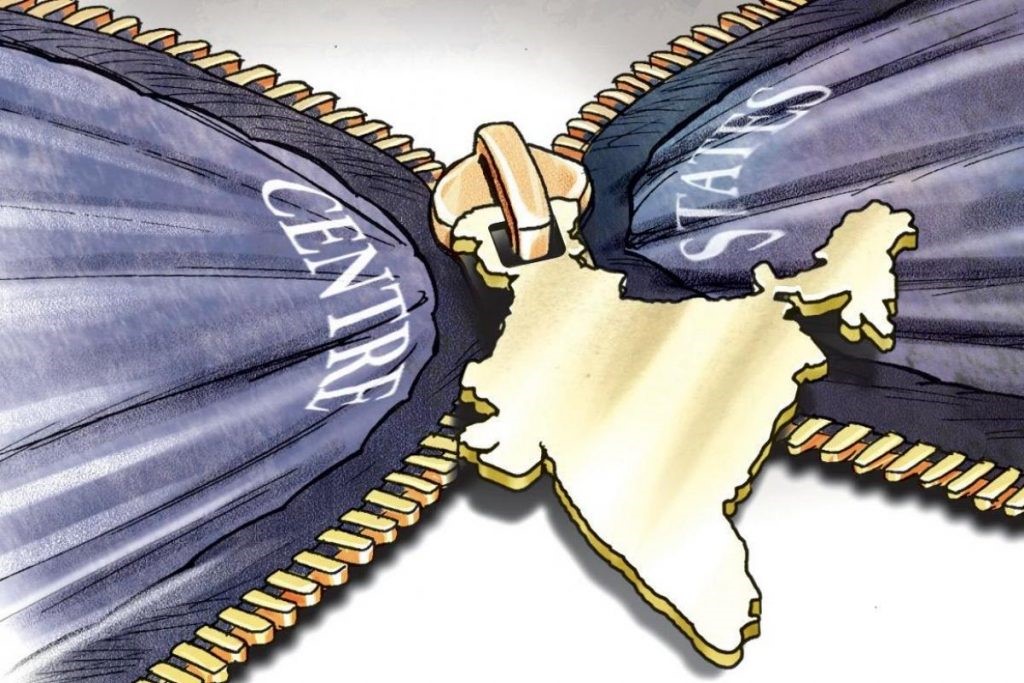

The Constitution of India is a federal document that divides all powers between the Centre and the states. These powers include legislative, executive, and financial. The Centre and the states are supreme in their respective spheres, but they must cooperate to ensure the smooth functioning of the federal system.

The Centre-state relations can be studied under three heads:

- Legislative relations

- Administrative relations

- Financial relations

Legislative Relations

- Articles 245 to 255 in Part XI of the Constitution focus on the legislative relationship between the central government and the states. In addition to these, several other sections also cover this topic.

- Similar to other federal constitutions, the Indian Constitution splits legislative powers territorially and subject-wise between the central government and the states.

- Constitution also allows for the central parliament to legislate in the state field under five exceptional circumstances and grants the central government the ability to oversee state legislation in specific scenarios.

Therefore, four key aspects shape the legislative relationship between the central government and the states, namely:

- Territorial extent of Central and state legislation;

- Distribution of legislative subjects;

- Parliamentary legislation in the state field; and

- Centre’s control over state legislation

Territorial extent of Central and state legislation

The Indian Constitution outlines the territorial extent of the legislative powers given to the Central Government and the States in below manner:

- Parliament is empowered to enact laws for any part or the entire Indian territory. This includes states, union territories, and any other regions presently within India’s territorial bounds.

- State legislative bodies have the authority to pass laws for their respective state or any section within it. However, these laws do not have jurisdiction outside the state unless there’s a substantial connection between the state and the subject matter.

- The power to enact ‘extraterritorial legislation’ is exclusively with the Parliament, extending its laws’ applicability to Indian citizens and their properties globally.

However, the Constitution imposes certain limitations on the Parliament’s territorial jurisdiction in the following situations:

- Article 240: The President holds the power to make regulations for the development, and governance of five Union Territories – Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, and Ladakh. These regulations equate to the force and effect of a parliamentary act, with the ability to repeal or modify any parliamentary act concerning these territories.

- Schedule 5(3) of the Indian Constitution: Governor has the right to direct that a parliamentary act does not apply to a scheduled area within the state, or it applies with certain modifications and exceptions.

- Similarly, the Governor of Assam can direct that a parliamentary act is not applicable to a tribal area (autonomous district) within the state, or it applies with particular modifications. The President carries the same authority over tribal areas (autonomous districts) in Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

Distribution of Legislative Subjects

The Constitution outlines a tripartite division of legislative topics among the central and state governments: List-I (the Union List), List-II (the State List), and List-III (the Concurrent List) located in the Seventh Schedule.

- Exclusive authority to legislate on matters listed in the Union List is given to the Parliament.

- Currently, there are 97 topics in this list, including defence, banking, foreign affairs, atomic energy, interstate commerce, auditing etc.

- Matters of national significance or those requiring nationwide uniformity are in the Union List.

- Under normal conditions, the state legislature has exclusive rights to enact laws pertaining to subjects in the State List.

- State List currently has 61 topics such as public health, local governance, agriculture, police, and more.

- The Parliament and the state legislature share the authority to legislate on subjects in the Concurrent List.

- Concurrent List currently has 52 topics like family planning, labour welfare, civil procedure, drugs, and others.

- Through the 42nd Amendment Act of 1976, five subjects were moved from the State List to the Concurrent List: Education, Wildlife Conservation, Administration of justice, Forests, and Weights and Measures.

- Subjects of regional and local significance or those allowing diversity are in the State List.

- Parliament holds the authority to legislate on any topic for any part of Indian territory not included in a state, irrespective of whether it’s listed in the State List. This mainly refers to Union Territories or Acquired Territories (if any).

- The 101st Amendment Act of 2016 introduced a special provision for goods and services tax, empowering both the Parliament and the state legislature to legislate on it.

- However, Parliament has exclusive power in cases of interstate trade or commerce.

- The power to legislate on residual subjects (those not included in the three lists) lies with the Parliament, including the authority to impose residual taxes.

Conflict between Subjects mentioned in Central, State and Union List

- The Constitution upholds the supremacy of the Union List over both the State and Concurrent Lists.

- In case of a clash between the Union and Concurrent Lists, the Union List should take precedence.

- Similarly, if a conflict arises between the Concurrent and State Lists, the Concurrent List should dominate.

- When there’s a dispute between Central and state laws regarding a topic listed in the Concurrent List, the Central law prevails over the state law.

- Exception: If a state law, after being reserved for the president’s consideration, receives his approval, then the state law will prevail within that state.

- However, it remains within the Parliament’s power to override such a law by later creating a law on the same topic.

Comparing with other countries constitution

- The Constitution of the United States specifies the functions of the Federal Government, leaving the remaining powers to the individual states.

- This single enumeration of powers approach was also adopted by Australia in its constitution.

- But Canada follows a dual listing system – Federal and Provincial, with the remaining powers resting with the central government.

- In 1935, the Government of India Act put forth a three-tier classification – federal, provincial, and concurrent.

- The current Constitution adheres to the structure outlined in this act, with a key distinction. Under the 1935 act, neither the federal nor the provincial legislature was granted the remaining powers; instead, they were given to the governor-general of India. Here, India aligns with Canada’s approach.

Parliamentary Legislation in the State Field

In normal circumstances, the legislative powers are divided between the central and state governments as per a specific plan. However, this distribution can be altered or even suspended during times of crisis.

The Constitution grants the Parliament the authority to enact laws concerning any subject within the State List under five unique situations:

1. When Rajya Sabha Passes Resolution (Article 249):

- If the Rajya Sabha determines it is crucial for national interest for the Parliament to pass laws relating to the goods and services tax or any topic in the State List, the Parliament gains the legal competence to do so.

- This kind of resolution needs support of two-thirds of the members who are present and participating in the voting process. The resolution can be upheld for a year and can be extended multiple times, but each extension cannot surpass a year. These laws become null and void six months after the resolution is no longer active.

- But if a conflict arises between a state law and a parliamentary law, the latter holds precedence.

2. During a Proclamation of National Emergency (Article 250):

- Under a national emergency, the Parliament gains the authority to pass laws relating to the goods and services tax or any subject in the State List.

- These laws become null and void six months after the termination of the national emergency.

- Similar to the previous circumstance, this does not hamper a state legislature’s ability to enact laws on the same subject. But if a conflict arises between a state law and a parliamentary law, the parliamentary law takes precedence.

3. When States Make a Request (Article 252):

- In situations where two or more state legislatures approve resolutions inviting the Parliament to pass laws on a topic from the State List, the Parliament is authorized to regulate that matter.

- Laws created this way apply solely to those states that have approved the resolutions. However, any other state can adopt it later by approving a resolution in its own legislature. This type of law can only be modified or repealed by the Parliament, not by the state legislatures involved.

- The result of such a resolution is that the Parliament gains the power to legislate on a matter that for which it has no power to make a law. At the same time, the state legislature loses its legislative power over that matter.

- Laws enacted this way are: Prize Competition Act (1955), the Wild Life (Protection) Act (1972), the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act (1974), the Urban Land (Ceiling and Regulation) Act (1976), and the Transplantation of Human Organs Act (1994).

4. To Implement International Agreements (Article 253):

- The Parliament has the authority to enact laws on any subject within the State List to implement international treaties, agreements, or conventions.

- This provision allows the central government to meet its international responsibilities.

- Laws enacted under this provision are: United Nations (Privileges and Immunities) Act (1947), the Geneva Convention Act (1960), the Anti-Hijacking Act (1982), and legislation relating to the environment and TRIPS (Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights).

5. During President’s Rule (Article 356):

- When a state is under the President’s rule, the Parliament gains the authority to legislate on any matter in the State List pertaining to that state.

- Even after the termination of the President’s rule, a law made by the Parliament remains operative.

- This means that the validity of such a law is not tied to the duration of the President’s rule. However, the state legislature can repeal, alter, or re-enact such a law.

Federal Oversight on State Legislation

Apart from the Parliament’s ability to directly legislate on state matters under extraordinarycircumstances, the Constitution bestows upon the Centre the power to supervise state legislative affairs in several ways:

- The Governor holds the authority to set aside specific types of bills passed by the state legislature for the President’s evaluation. The President wields complete veto power over such bills.

- Certain types of bills that fall under subjects listed in the State List can only be introduced in the state legislature with the President’s prior approval. This includes bills that place limitations on the freedom of trade and commerce.

- During a financial emergency, the Centre can instruct states to reserve financial bills, including money bills, passed by the state legislature for the President’s review.

Conclusion

Center and state relationship in legislative domain is a delicate balance, designed to ensure unity in diversity. The constitutionally mandated supremacy of the Centre, particularly in matters of national importance, coexists with the state’s exclusive rights on subjects of local significance. This power sharing serves as a testament to the dynamism of the Indian federal system, providing a robust framework for the evolution of Centre-state relations in an ever-changing socio-political landscape

Ref: Source-1

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What are the three lists of subjects in the Indian Constitution?

The three lists of subjects in the Indian Constitution are the Union List, the State List, and the Concurrent List. The Union List contains subjects that are under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Parliament of India. The State List contains subjects that are under the exclusive jurisdiction of the State Legislatures. The Concurrent List contains subjects that can be legislated on by both the Parliament and the State Legislatures

What is the legislative relation between the centre and the states in India?

The key legislative relations between the centre and the states in India include territorial jurisdiction of legislation, distribution of legislative subjects, parliamentary legislation in state field, and Centre’s control over state legislation

What is the importance of the legislative relations between the Centre and the States?

The legislative relations between the Centre and the States are an important part of the Indian federal system. They ensure that both the Centre and the States have a say in the laws that govern India. This helps to ensure that the interests of all parts of India are represented in the law-making process.

Can the Centre intervene in the legislative matters of a state?

Yes, in exceptional circumstances such as a national emergency, or when the Governor reserves certain bills for the President’s consideration, the Centre can intervene in state legislation.

How can the Centre and the States cooperate on matters of common interest?

The Centre and the States can cooperate on matters of common interest by entering into agreements with each other. The Centre can also give financial assistance to the States to help them carry out their legislative functions